The theatre of our research is the Pollino National Park spanning across the regions Basilicata and Calabria. The park is characterized by the Pollino and Orsomarso massifs that are part of the southern Apennine mountain range. Covering more than 192 thousand hectares, it is the largest national park in Italy. Our research is limited to the highlands in the central part of the Pollino range.

The Park obtained its protected status in 1993 and the status of UNESCO Geopark in 2015. Besides its spectacular geology, the park is also known for its flora and fauna, and attracts many visitors each year. One of its main attractions is the Pino Loricato (Pinus Leucodermis Ant.), an age-old robust pine tree that grows on the steep limestone slopes.

History

The history of the Pollino is a history of mobility. The Park is situated at a relatively narrow part of the Italian peninsula, with short distances to both the Ionian and the Tyrrhenian Seas. As such, the area has always functioned as a gateway between the south and the north, as well as the east and west. Whether hunter-gatherers following migrating herds, Neolithic and Bronze age peoples in search of specific resources, or Italic shepherds leading their flocks to the uplands for summer grazing and, more recently, transhumant shepherds and charcoal burners: humans and animals have moved through this region for thousands of years, using the same routes as one does today when visiting the park. Here we shall give a brief history of humans and the Pollino.

300.000 – 48.000 BCE

The human history of the Pollino begins long before the arrival of modern humans (Homo sapiens). Incidental finds of stone tools demonstrate the presence of archaic humans in the park at least since the Middle Palaeolithic (ca. 300,000-48,000 BCE), and perhaps even earlier. These people were nomadic hunter-gatherers who hunted wildlife on the mountain plains, collected edible plants in the forests, and dwelt in the limestone caves.

48.000 – 11.000 BCE

Modern humans have lived in the area since the Upper Palaeolithic (ca. 48.000 BCE). This was a period of substantial climate variations, which also affected the hunter-gatherers in our area. Over longer periods the Pollino mountains were covered by glaciers and therefore inaccessible. In the warmer periods, hunter-gatherers followed the wildlife on their seasonal migrations into the mountains. Their connection with the wild animals on which they relied can be seen in the Palaeolithic rock carving of the aurochs (Bos primigenius) in the Romito Cave. One can easily imagine humans ambushing and hunting these large beasts on the wide pianori of the Pollino.

11.000 – 6.000 BCE

After the last ice age and the beginning of the Holocene (ca. 11.000 BCE), the Pollino mountains became more accessible. From other parts of Italy, we know that the last hunter-gatherers (during the Mesolithic, ca. 11.000-6.000 BCE) became more specialized in distinct subsistence strategies. Their stone tools also became finer and smaller than those of their Palaeolithic predecessors. So far, we have no evidence for Mesolithic people in the Pollino highlands. This may be because they focused on hunting and gathering at lower altitudes, but it may also be that their traces are very difficult to find for archaeologists.

6.000 – 3.000 BCE

In the 7th millennium BCE, new groups of people entered Italy, arriving first in the South (the Neolithic, ca. 6.000-3.000 BCE). They introduced agriculture, animal husbandry and (semi-) sedentary habitation. With this new lifestyle came the need for pasture, building materials, and other natural resources. All this could be found in the highlands of the Pollino. Human activity, and its impact on highland nature, is best seen in the changing vegetation record. Archaeologists reconstruct this using soil samples from former lakes filled with plant material, of which we have several in the Pollino. Occasional finds of stone tools and pottery show the presence of early farmers in the highlands, which possibly indicates the first evidence of (short distance) livestock mobility. However, these activities still had little impact on the vegetation.

3.000 – 1.000 BCE

Archaeological investigations have shown that there was a substantial increase in settlement activity in the upper valleys of the Raganello basin during the Bronze Age. The valley around San Lorenzo Bellizzi was especially favoured for small-scale farming by Bronze age communities. They used the highlands of the Pollino for grazing their flocks during the summer, but they also hunted for wildlife. Occasional finds of pottery on the Piani di Pollino show that these activities must have played an important role in their subsistence. In the course of this period the landscape becomes more open, likely due to summer grazing.

1000 – 272 BCE

The Iron Age, Archaic, and Hellenistic periods see the rise of urban centres and the intensification of indigenous habitation in the foothills. This period is also marked by the arrival of Greek colonists that settled on the Ionian coast, and the foundation of the Greek city of Sybaris in 720 BCE. At the end of the Bronze Age (ca. 1.000 BCE), archaeologists see the abandonment of settlements in the Pollino inlands. Although people moved further away from the mountains, the population increase in the lowlands put more pressure on available grazing land. Sheep and goats remained important to Iron Age communities not just for subsistence, but also for the creation of woollen textiles. This led to the creation of livestock mobility over longer distances (middle-distance transhumance).

272 BCE – 476 CE

At the end of the Pyrrhic war in 272 BCE, the region was incorporated into the Roman Republic. This connected the Pollino area to the Roman market economy, which saw systematic trade over large distances. An important trade artery ran across the Campotenese pass in the Pollino massif, connecting Campania in the north and the Calabria peninsula in the south. With the arrival of central organisation and regional stability also came the practice of long-distance transhumance, executed by professional shepherds, leading large herds. We still have little direct evidence for Roman presence in the Pollino highlands, but our vegetation studies show strong environmental impact and erosion related to (over-)grazing.

476 – 1447 CE

The Pollino range remained part of the Roman empire until the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE. This year marks the beginning of the Middle Ages and the beginning of a tumultuous time for the Pollino region. It came under control of the Eastern Roman Empire in the 6th century CE. Beside the Byzantines its control changed hands often throughout the Middle Ages, among others to Lombardic, Saracenic, and Norman rule. The loss of central control and regional stability meant, for a large part, the end of long-distance transhumance and an interregional trade network. Furthermore, the Pest epidemics in the 13th century led to a sudden population decrease and a rewilding of the mountain inlands.

1447 – 1861 CE

The practice of long-distance transhumance slowly returned in the 15th century under Spanish rule of the Kingdom of Naples, of which the Pollino region was part. The Spanish king provided transhumance routes with a protected status under the Regia Dogana. This marks the beginning of the traditional livestock mobility practices that are now considered Italian cultural heritage. Several main transhumance routes crossed the Pollino highlands.

1861 – 1993 CE

After the Italian Unification, the region experiences multiple migration waves to America. The population drops considerably as well as the sizes of the livestock herds. The practice of transhumance and the use of the Pollino highlands rapidly declines, but stays in continuous use. Shepherds live in the mountains during the summer and move down the valley in winter. This practice ends in 1993 when the area gains the status of a protected national park. Despite the fact that no one lives in the Pollino highlands anymore, some families still keep cattle herds in the mountains in summer.

1910 – 1933 CE

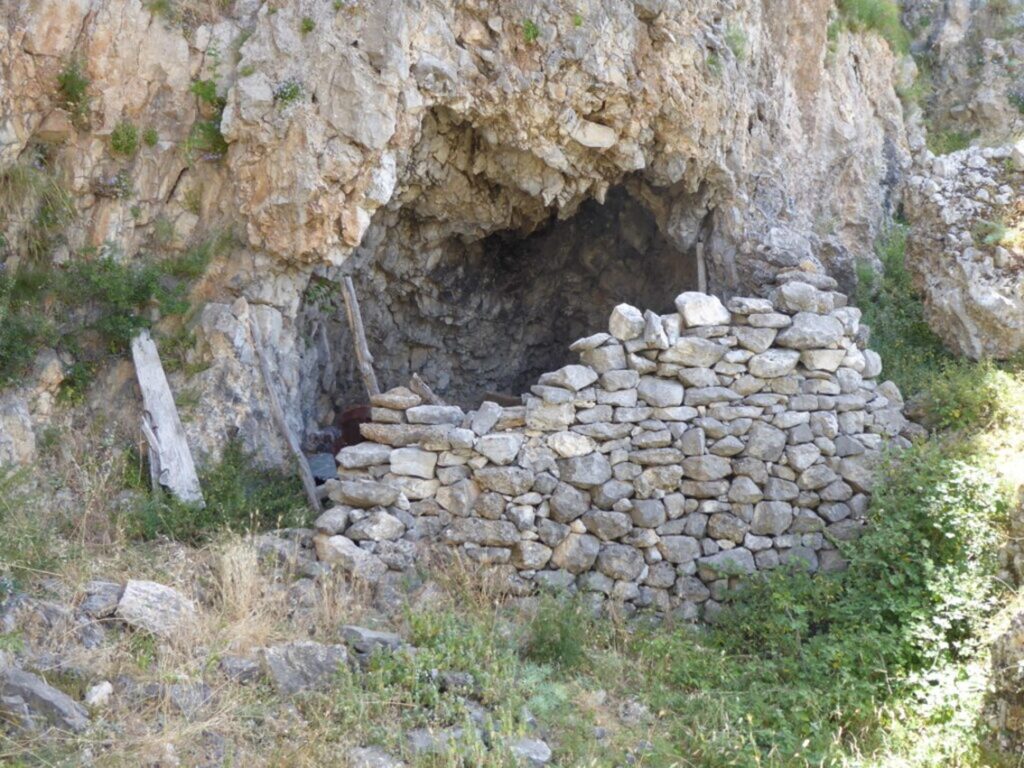

In 1910, the German logging company Rüping acquired logging rights on the Pollino. The ancient beech tree forests were felled by local workmen, 600 of whom worked for the firm in Calabria. They continued logging until 1933, but traces of the logging company are still visible in the forests of the Pollino. These include house plans, large pits, railway tracks, and the foundation of the lifts used to carry logs down from the Grande Porta and the Manfriana. In the 1950s, the firm Palombaro took over the logging rights. Charcoal burning was also practiced on the Pollino. We still find charcoal burning platforms and small drystone buildings once inhabited by carbonai and their families.

1993 CE – Now

The Pollino and Orsomarso mountains gained their protected status as a national park in 1993, thereby becoming the largest national park in Italy. The park spans the border region of Basilicata and Calabria. The newly acquired status of the park meant that shepherds could no longer live in seasonal camps on the Pollino. However, some obtained permits to use the pastures for grazing, allowing the practice of seasonal upland pastoralism to continue.

In 2015 the park gained the status of a UNESCO Global Geopark.